A Long Read (estimated 25 minutes)

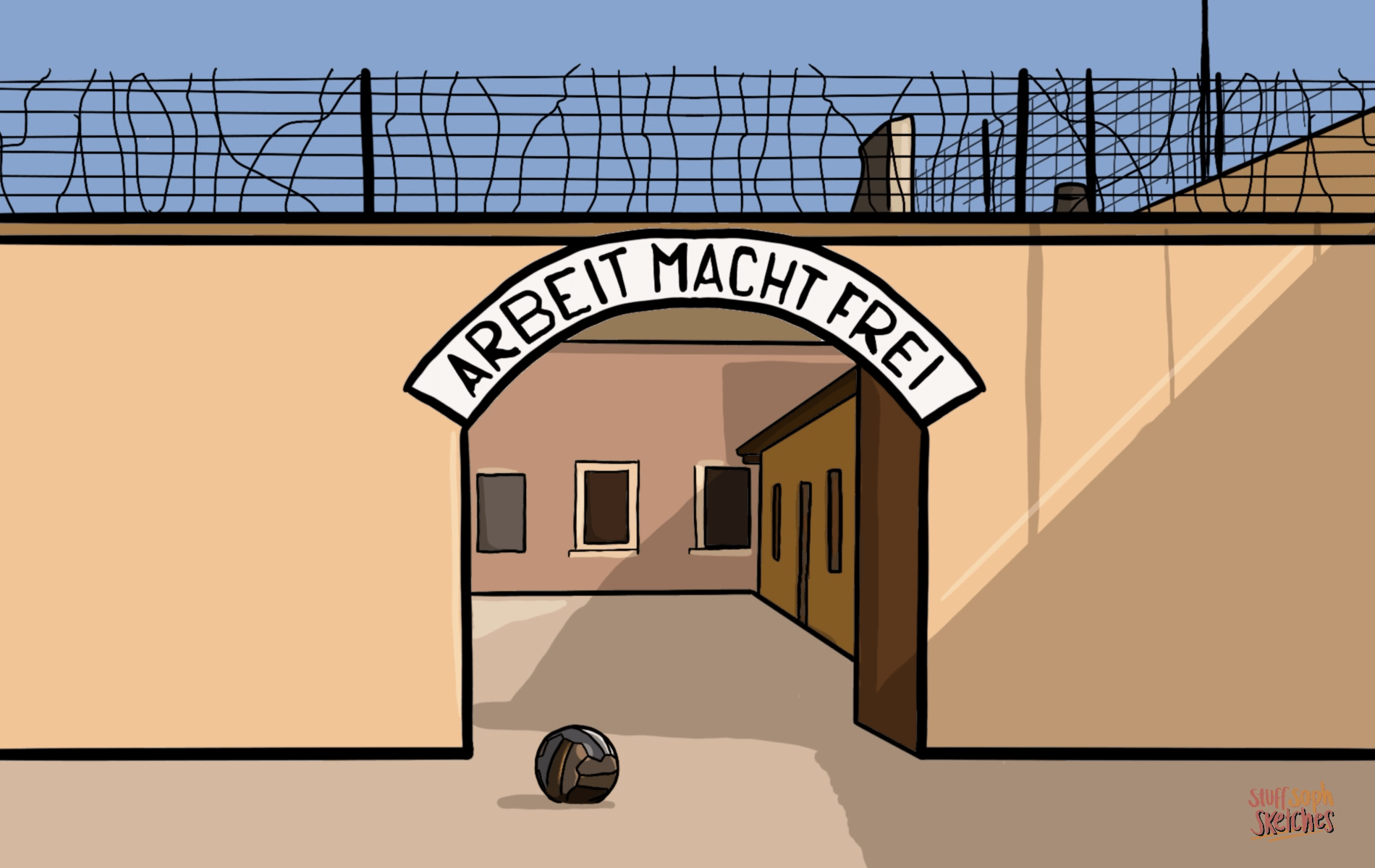

Since the ancient civilisations, and at least the eighth century in England, people have participated in some form of a game that involves kicking a ball. One of the most surprising places where football has been practised was within the Nazi concentration camps and ghettos of the twentieth century. Here, football was occasional and was primarily incentivised as a reward for uplifting the work ethic under the infamous slogan ‘arbeit macht frei’ (work sets you free). Theresienstadt, however, was an exception. As most of the European football competitions were postponed after the outbreak of war in 1939, the Theresienstadt ghetto in occupied Czechoslovakia was one of the few places that maintained a structured and competitive form of football. From spring 1943 to the latter stages of 1944, Liga Terezín, as it was known in Czech, fostered a first and second division, seasonal cup competitions, exhibition matches, and even a youth league. Despite being held under the authority of Hitler’s SS, the Jewish community imprisoned within the concrete walls of Theresienstadt would come to establish one of the most remarkable, yet unknown, football competitions in history.

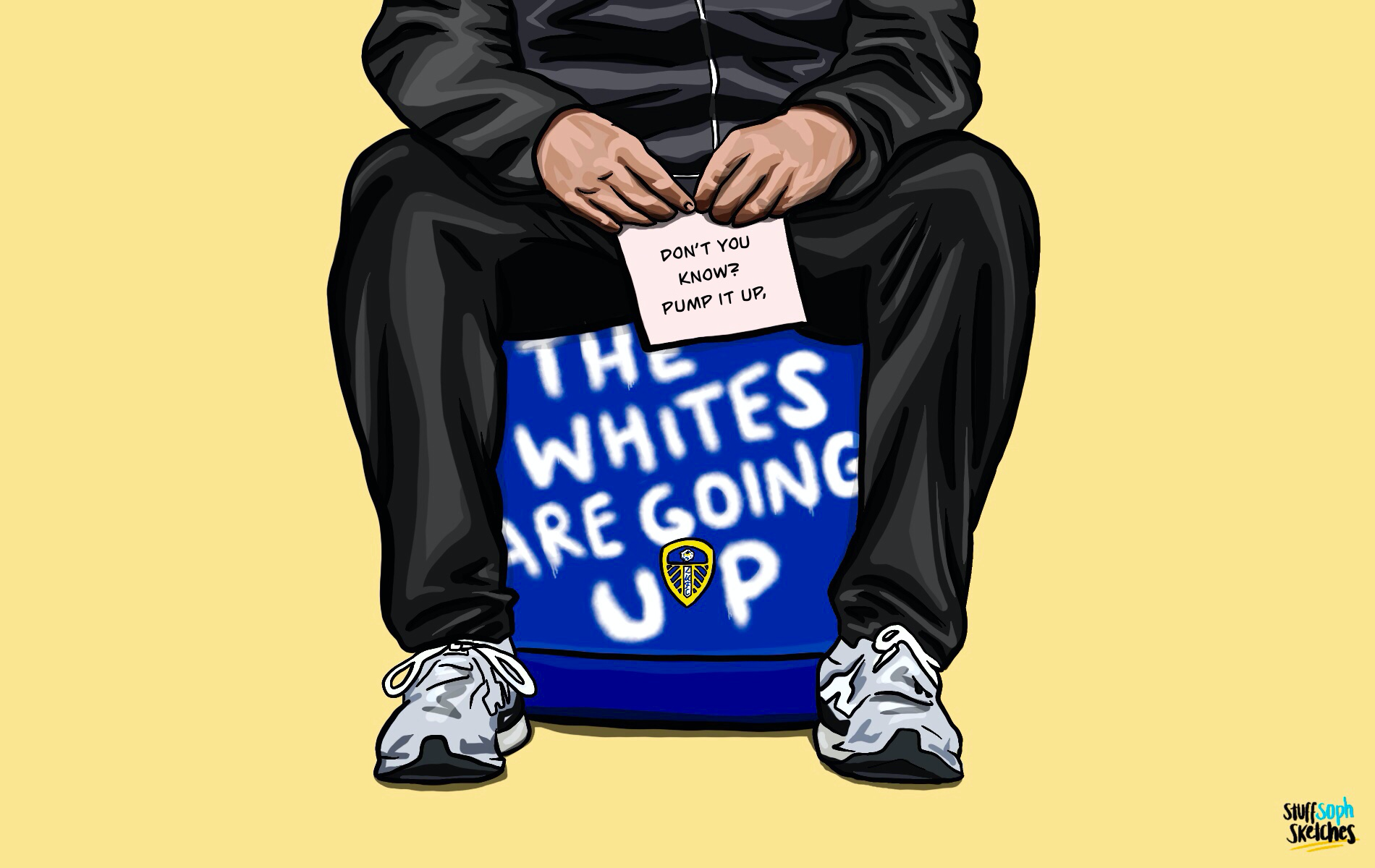

Football was a kind of comfort in Hell’s waiting room.

Located forty miles north-west of Prague, Terezín is a small Czech town and former military fortification. Constructed in 1780 by the Habsburg Emperor Joseph II, the settlement was built to contain a walled citadel in defence against the Prussians. Administered by Nazi Germany from November 1941 to May 1945, Terezín (or Theresienstadt in German) was the only ghetto established in the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia during the war. On 10 October 1941, Reinhard Heydrich (chief of the Reich Security Main Office) proposed that the pre-existing fortress would be the ideal place to confine the Czech Jews as part of the persisting “Jewish Question”. On 24 November 1941, the first transport of 340 men arrived to prepare the area for the increased incarceration of Jews from Germany, Austria, Czechoslovakia, the Netherlands, Denmark, Slovakia and Hungary over the next four years.

Theresienstadt later became a literal and direct link in the “Final Solution”, allowing the Nazis to concentrate Jews before sending them eastwards to the extermination camps – the likes of Treblinka and Auschwitz in Poland. Upon its liberation on 9 May 1945, approximately 155,000 men, women, and children had passed through; some 35,000 Jews perished within the ghetto and a further 83,000 were believed to have been killed in the east. How then, under these circumstances, were prisoners able to play football?

Fearing unwanted attention should the majority of Europe’s Jews disappear, including many accredited celebrities and cultural icons, Theresienstadt became an exception because of its tolerance. Unlike the camps and ghettos elsewhere, the SS permitted religious and artistic expression, sport, and even some external correspondence. Today, Theresienstadt is remembered for its prodigious cultural output, including theatre, artwork, poetry and music but its football is often forgotten.

As guarding was performed by Czech gendarmes (there were no more than thirty SS personnel in Theresienstadt at any one time), daily administration was left to an elected Jewish self-government. The self-administration consisted of a Council of Elders who were accountable for transmitting SS orders. Together, the Council created a network responsible for all areas of daily life. There existed nine main departments covering everything from health, economics, recreation to youth welfare. Liga Terezín developed as the ghetto resembled a highly organised society to begin with.

Under a weak SS presence, inhabitants sought to occupy themselves wherever possible; sport was one of the few options available when not working towards ghetto maintenance. Spontaneous “kick-abouts” emerged as a reprieve from boredom and a distraction from the unprecedented situation. Former Czech international and Liga Terezín superstar, Paul Mahrer stated that ‘football was a kind of comfort in Hell’s waiting room’. At the time, Czechoslovakia and Austria had outstanding national teams and a lively football culture that encompassed all, including Jews. With the Council’s desire to establish a functional community, it did not take long for football to be incorporated into the Recreation Department.

On 8 April 1943, the Recreation Department created a certified football committee comprised of former professionals and high-ranking members of the Jewish community. The football association developed a functional, almost professional system containing three divisions (a two-tiered adult league and a youth competition). In accordance with the climate, a year would consist of two separate “seasons” played in spring and autumn. At the end of each campaign, two teams from the lower league earned promotion and the two worst performing sides from the top division were relegated. Points were awarded for wins, draws and losses as expected. The Council enforced centralised regulations, even ensuring that a doctor was available for every game. Matches lasted two thirty-five-minute halves with teams consisting of seven players each because of spatial restrictions. The committee sourced thirteen former-professional referees, among them were some of Europe’s most renown officials such as Otto Dörfler and Paul Heller, who whistled 110 matches alone. In 1943, these referees directed an exhausting total of 778 adult and 512 youth encounters on both a “professional” and amateur level. Results were published near the Magdeburg barracks, the seat of the self-government, and high-stakes games were ceremonially opened by a Council delegate. The unconditional support of the Council proved that football was worthy of investment, cementing the sport as a customary part of every-day life in the ghetto.

The first formal squads derived from the ghetto’s work details, including the Cooks, Butchers, Electricians, Gardeners, Youth Welfare and Clothing Warehouse. Work-based teams were a simple way to categorise players. As football became popular, new teams emerged and others renamed themselves after famous teams such as Arsenal and particularly the Czech clubs of Sparta and Slavia. The Clothing Warehouse, winners of the first spring season, would go on to dominate under the name of SK Sparta, who were admired enough to run an additional youth team and won six of the twelve major tournaments hosted in Terezín. “Hagibor” and “Maccabi” were also popular names inspired by existing Jewish teams and youth movements. Terezín was a site of transnational encounters which meant that “national teams” quickly emerged. Many of the Czechs played for Bohemia, Moravia, or Prague-centric teams, the Germans clung to Köln and Union, the Austrians chose Rapid and Wien (Vienna), and Hollandia (the Netherlands) materialised after the arrival of the Dutch transports. From the beginning of 1943 to the end of 1944, more than thirty-six certified teams represented the miscellaneous ghetto demographic.

Liga Terezín showcased an array of former professionals sent to the ghetto from the prosperous footballing nations of Czechoslovakia, Austria and the Netherlands. Among them were Jirka Taussig (DFC Prague and Czech international), Egon Reach (DFC and Reichenberger FK) and Ignatz Fischer (SC Hakoah Vienna, FK Austria Vienna and FC Baník Ostrava). These names are often the focal point of eyewitness accounts. To begin with, a player’s relationship to a team was not strictly exclusive. Fischer played for Vienna and Sparta before being selected for an “All Stars” exhibition match at the second anniversary of Terezín. Spectators did not criticise players for representing multiple clubs as they wanted to see the superstars where possible. René Tressler even went on to sign for Sparta Prague after the war, certifying Theresienstadt’s talent.

Surviving league tables uncover a pattern of high scoring fixtures. In Autumn 1943, twelve teams participated and there were no nil-nil draws in sixty-six games; there were only three clean sheets with 562 goals in total. The Cooks were the winners, finishing just three points above the Clothing Warehouse as reigning champions. The fact that league tables were even produced is evidence that the football association and the ghetto populace took the game seriously. In the interests of fair play, a weekly transfer window was introduced every Monday meaning players could no longer represent several sides. The true intention behind the transfer policy, however, was to cater for the ever-changing line-ups with many being sent to the death camps in the east. The popularity of the best matches in Terezín translated into a demand for added competitions after summer 1943, including a Youth Cup and Stadtpokal (City Cup). In 1944, a Superpokal (Super Cup) was introduced between division and cup champions as well as a knock-out tournament featuring thirty-two teams of all levels. Summer and winter cups were eventually established making football incessant throughout the year.

There were four main sites where football occurred in Theresienstadt. The most prominent areas were the large stone barracks of Dresden, Magdeburg, and Hanover. The barracks were ideal to host football matches because they were fully enclosed, had viewing windows, and a rectangular courtyard at its centre. Across eyewitness accounts, Block HV is commonly referred to as “the Dresden Stadium”. The turf was not so accommodating as surfaces consisted of clay and pebbles and the less favourable Hanover barracks was covered by cobblestones which could easily cause injury (a frightening prospect given the circumstances). According to the regulations of the International Football Association Board (IFAB), the minimum size for a pitch is ninety by forty-five metres. While Hanover was smaller, Magdeburg and Dresden measured eighty by forty metres, thus were the most suitable venues for the respected adult tournaments. Considering the existing parameters, the goals had to be smaller and teams were limited to seven players a side. The barracks-based matches that typified Liga Terezín attracted spectators from all generations. In the first nine months, it is estimated that 144 league and cup matches were watched by 300,000 spectators, averaging 2,083 per match. The last official championship game (Youth Welfare versus Freight Forwarding) took place in Dresden on 26 August 1944 with a record 7,500 spectators. The match ended in a 2-1 victory for Youth Welfare, making them the last league champions in autumn 1944.

The fourth location frequented by footballers was at the ghetto’s periphery; the most popular site was Südberg. These grasslands contrasted the town’s concrete courtyards, although little grass was actually present. Südberg is commonly referenced in the testimonies of former children for it was located behind the youth barracks. Here, the Youth League and Cup competitions took place alongside leisurely play during free time. For the children in particular, football on the peripheral hills embodied hope and liberty.

The desire to emulate a sense of normality was commonplace and football was a welcome distraction from the universal fears of everyday life. Survivors are predominantly optimistic when discussing sport because it is more appealing than reliving moments of suffering. Youth Welfare superstar, Honza Burka acknowledges football as a momentary escape, emphasising that ‘Sunday was a special day because we could forget our misery for just a few hours’. On the other hand, goalkeeper and teammate, Franta Maier admits the frivolity of football for the inhabitants ‘played twice a week, and that was nice, but we were worried most of the time by different problems,’ namely, how to protect a healthy population in an overcrowded disease-ridden ghetto.

Football was not entirely constructive either for the sport exacerbated the hierarchical social structure of the ghetto. Firstly, one needed the right personal connections or a respected position within the community to be invited to play for a team. Experienced footballers were placed in a privileged position effective immediately. As a well-known goalkeeper, Taussig claimed that ‘people knew that I was being transported from Prague because several teams fought over me when I arrived’. Taussig represented the Clothes Department and was partially responsible for their success as the first league champions. Author and former Theresienstadt player, Arnošt Lustig notes that it was not uncommon to see ‘officials inspect the transport lists leaving the ghetto so they could take off former players’ and keep them in Terezín. Maier maintains that ‘we were adored like soccer players and rock stars are today…when you entertain and excite, this is only natural’.

It was not uncommon at the Dresden matches to find that the majority of the supporters were women as this was their sleeping quarters. True to the times, women were unable to practise football seriously in the patriarchal society of Terezín. Although they were permitted to play freely at Südberg, there was no league or officiated matches for women; they were present as enthusiastic supporters or league seamstresses. In the textile workshops, women manufactured distinct uniforms and pennants for the popular teams. Prohibiting women from participating in Liga Terezín is just another example of the exclusivity of football in Theresienstadt.

Football equally gifted players material gains that aided survival or more comfortable living. The insufficiency of food tormented the inhabitants on a daily basis. The allocation was never more than a thousand calories per person per day (the average for an adult male is 2,500 calories per day). Typical “meals” consisted of a black coffee substitute in the morning, watery soup for lunch and the same in the evening. These rations were inadequate for a healthy individual working a minimum of fifty-two hours per week maintaining the ghetto. Predictably, the Butchers, Gardeners and Cooks thrived because of their access to food. Aside from mustering their own strength, Milos Dobry admits that the Butchers managed to seduce experts like Paul Mahrer for ‘food became his salary’. Football was limited to the most athletic prisoners, those fit enough to withstand the strains of daily life. Ironically, the healthiest sportsmen were given extra supplies whereas the overwhelming majority grappled with death. Yet, the opportunities to play declined with the shifting fortunes of war and a privileged status did not always protect players from liquidation. The final transports of September and October 1944 would come to prove that footballers were certainly not invincible.

Eyewitness reports reveal that even the SS were caught-up in the excitement of Liga Terezín. Burka recalls the ‘centre box’ on the first floor of the Dresden barracks that was ‘kept for the SS, like the best seats at the theatre’. Unfortunately, the ghetto was the scene of all forms of corruption to which football contributed. The SS may have enjoyed football as a cruel form of “sport” in itself for they often placed wagers, betting on the games as if watching horseracing or cockfighting. Yet, the prisoners could use this interest to their advantage, gaining access to food, contraband cigarettes, and other basic provisions. Arguably, football was a spectacle that had the potential to break down the adversarial relationship between inmates and authority, temporarily at least.

Alongside other aspects of Theresienstadt culture, football was a prisoner-led development that was exploited by the SS. In preparation for the International Red Cross visits on 23 June 1944 and 6 April 1945, the Nazis ordered the prisoners to embark on two beautification campaigns to disguise the ghetto as a comfortable “Jewish Settlement”. Prisoner and former director, Kurt Gerron was ordered to create a documentary (commonly known as The Führer Gives a City to the Jews) which included lengthy scenes of football being played. The SS realised that people all over the world liked football and its inclusion was thought to make the people’s acceptance of Nazism easier. The match recorded on 1 September 1944, viewed by 3,600 spectators, was the Super Cup final between Youth Welfare and the Clothing Warehouse. The film captures reams of people jovially filing through the Dresden barracks, perching in every vantage point and lining the “stadium”. The teams run onto the field together as the camera picks up the roar of elated cheers with a palpable focus on the faces of delighted children. Conveniently, there are no Nazis present.

Within six weeks, all of the witnesses visible in the film (including its director and much of the Council) were transported to Auschwitz-Birkenau in an acceleration of the Final Solution. Liga Terezín was dismantled after losing almost all of its regular players and fanbase in the final transports of September and October 1944. The film itself had no effect on the thinking of the few who actually saw it, both domestically and abroad, given that the fate of the European Jews was no longer a secret. Today, the film is far more important as physical evidence. Despite the propagandistic intentions, Gerron’s film verifies the genuine enthusiasm for football and forms part of the legacy of Liga Terezín.

There is truth in Dobry’s belief that ‘he who plays, is he who lives’ in Theresienstadt; football aided survival in that it provided resources and protection for prized players. However, football represented far more than the semblance of normality and a distraction from the ever-present threat of the east. Liga Terezín was an integral part of a larger social agenda administered by the self-government that aimed to protect and structure a functional Jewish community. Football did not just satisfy the temporary needs of the people either for it was developed in order to prepare for a healthy Jewish future in the post-war world. Ultimately, investing energy in the organisation, playing or watching of football was an active demonstration of Jewish agency in a malevolent system that sought to destroy it.

For further reading on this topic see František Steiner’s Fußball unterm gelben Stern: Die Liga im Ghetto Theresienstadt 1943-44, translated by Stefan Zwicker (2017).