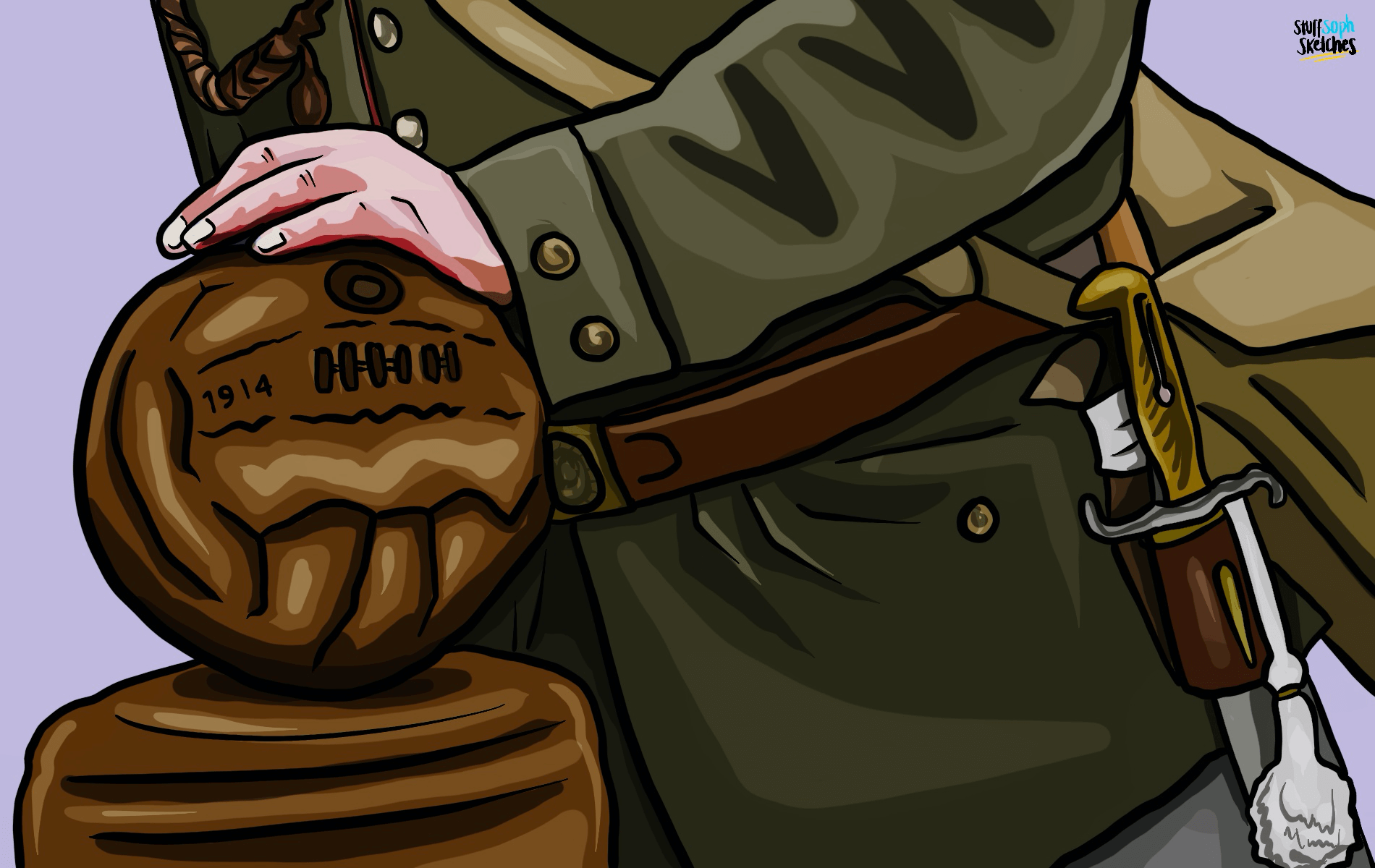

In 2014, to mark the centenary of the First World War, Sainsbury’s launched perhaps the finest Christmas advert to date. Made in partnership with The Royal British Legion, the three-minute advert depicted the famous “Christmas Truce” – a rare stalemate from the horrors of trench warfare on 24 and 25 December 1914. Far more emotive than Aldi’s anthropomorphised carrots or that cute John Lewis Penguin, Sainsbury’s pitched the Germans and English happily standing side-by-side, sharing family photographs, laughing, smiling and, of course, playing football. The Christmas ceasefire has since become one the most well-known and widely mythologised events of the First World War, but did the soldiers really play football on the boggy, bombed-out turf of no-man’s land on that unique Christmas day?

Legend has it that late upon Christmas Eve 1914, the British Expeditionary Force (BEF) heard German troops jovially singing carols and merrymaking from the opposite trenches. There are even reports of small fir trees lining the enemy’s barbed-wire fences and decorated with lanterns. The German’s were believed to have initiated the festivities due to the fact that their clocks “back home” would have been set an hour earlier than those of the British and French. Messages and jokes were later shouted between the rival trenches and a ceasefire was eventually agreed – fear and apprehension eased as the soldiers relaxed in moment of temporary reprieve while songs continued long into the night in time with the spirit of the season.

Football was a powerful symbol of humanity and freedom – for a short while at least. .

The following morning, British and German troops met in no-man’s land, nervously but unarmed. The soldiers supposedly spent the day exchanging gifts as well as eating and drinking what they had. They took and shared photographs – some of which are displayed at the Imperial War Museum (IWM) today – and many excitedly played impromptu games of football. Naturally, some of the day was spent repairing each other’s trenches, attending to the casualties together, and burying the dead on both sides. By Boxing Day, however, the truce was over. The bloodbath was to resume for another four gruelling years, right up until the official German surrender on 11 November 1918.

At first, what appears so remarkable about this event is that it was not widely observed along the Western Front; it seems to have been a localised affair. According to reports, a number of officers believed that such a truce would undermine the fighting spirit and might give greater cause for desertion. But, in truth, ceasefires of this kind were not unique – dampening the Christmas magic somewhat. Representing the “live and let live” initiative, these minor pauses encouraged small-scale fraternisation – conversing, bartering and the like – which would simultaneously allow the opportunity for both sides to retrieve their dead and repair any defences in preparation for prolonged combat. The Christmas truce was not the first ceasefire, but it was certainly one of the last. Many naively assumed that the conflict would be over by Christmas, but after a year of fighting, the High Commands on both sides tried to prevent further armistices in accordance with the principles of “total war”. Nevertheless, isolated incidents still occurred, and not only at Christmas time. But did anyone actually think to bring a football to trenches?

The first reports that indicate such a contest, some form of semi-organised football, surfaced as early as 01 January 1915. Written by a doctor attached to a Rifle Brigade, The Times published a letter reporting that ‘a football match [had been] played between them and us in front of the trench’ on Christmas day. On the home front, this news was met with both joy and disgruntlement in equal measure for such a “sporting gesture” (in both senses of the word) was far from a conventional expectation during wartime.

Similarly, eyewitness testimonies appear to validate the football claim. Stationed near Ypres in Belgium, Ernie Williams (Sixth Battalion of the Cheshire Regiment) remembers “from somewhere, somehow, this football appeared. It came from their side, not our side. A proper football. They took their coats off and put them down as goalposts, but we didn’t form a team in any sense of the word. It was a kick-about”. Williams continues to suggest just how widely appreciated this moment of respite was, stating that “everybody was having a go. I should think there was at least a couple of hundred taking part. I had a go at it – I was pretty good then at nineteen”. Unsurprisingly, the woeful conditions meant that the game was not of a particularly high calibre for “the boots were a menace” and “the leather ball soon got very soggy”. Williams explains that “it was like playing as a kid in the streets. There was no referee and no score, no tally at all – it was simply a melee. Nothing like the football you see on the television”. But the standard didn’t matter. In that moment, football was a powerful symbol of humanity and freedom – for a short while at least.

Corresponding reports also exist from the away end. Lieutenant Johannes Niemann (Saxon 133rd Regiment) tells of a match between the Germans and the Argyll and Sutherlands Highlanders as deployed by the BEF. He remarked that “a Scottish soldier appeared with a football, which seemed to come from nowhere, and a few minutes later a real match got underway”. Like Williams, Niemann was surprised by the soldiers’ spontaneous turn to sport at such time and his match unravelled in a similar fashion. He recalls that “it was far from easy to play on the frozen ground, but we continued, keeping rigorously to the rules even without a referee”. He notes that the match lasted only an hour but “even though we were very tired, we played with huge enthusiasm”. The game finished with a score of “three goals to two in favour of Fritz against Tommy”.

Robert Graves, celebrated author and poet (and frontline officer at the time), later reconstructed the match between the Germans and the Scots as detailed by Niemann in a short story titled a ‘Christmas Truce’ (1962). The fact that Graves did not arrive in France until early 1915, however, suggests that he was not there and was simply responding to the accounts of those who were. His fictionalised story goes on to portray a second Christmas truce in 1915 whereby the same two battalions meet once again.

Despite such stories, Professor Mark Connelly from University of Kent believes that “the evidence is too hazy to say with any kind of certainty that a match took place”. After examining copious sources from the IWM, including correspondence between soldiers and loved ones, Connelly argues that there are minor references to “loose plans to play a game – but it seems they never actually got around to it”. It is fair to say that this story is one that has been fabled, embellished and exacerbated in popular post-war culture. Connelly admits that “there is enough evidence to suggest that someone kicked a ball at some point during the day”, but whether or not this can be rightfully considered “a match” is still up for debate.

A match or a kick-about. No goals or five goals. Referee or no referee. Ultimately, it doesn’t matter. In my opinion, there is enough evidence to suggest that a ball was kicked on 25 December 1914 between both German and British soldiers alike. Albeit prone to artistic overstatement, this seemingly trivial moment is a reminder that even during the direst circumstances, genuine human connection (and football) is what Christmas is all about.

Merry Christmas from all at The Rondo.