In 2010, UEFA announced plans to implement their Financial Fair Play regulations. Simply put, a football club’s outgoings in transfer fees, wages and dividends would be counted against their incomings from gate receipts, transfer fees, advertising, prize money, merchandising, television revenue and disposal of fixed tangible assets. Football clubs were meant to begin running at operating costs that kept their debt down to no more than €5 million over three years.

In 2019, Bury Football Club (who were playing in League Two at the time) became the first team since Maidstone United in 1992 to be expelled from the English Football League (EFL) due to their financial situation. On 27 August, with no way of paying their £12.5 million debts, the Football League withdrew Bury’s membership, resulting in thirty-one playing staff and numerous other people losing their jobs, as a club that was 134 years-old fizzled out of existence.

The history of our sport is littered with tales of clubs that gambled and ultimately lost.

Less than a year later, eight Premier League clubs were reported to be over UEFA’s FFP operating cost threshold. Currently, Derby County (playing in the Championship) are believed to be more than £60 million in debt, while FC Barcelona of La Liga are closer to £1.2 billion. Financial Fair Play? Who are you kidding, UEFA?

I do not wish to see any club go out of business, even Derby County (despite being a Nottingham Forest supporter!). Barcelona and Derby are both wonderfully historic clubs, whose existence enriches the footballing landscapes that they are a part of. But surely this sport that we love needs to take a good hard look at itself. Football exists for everyone and should not be exclusively for the rich. Since 2010, Bury, Rushden & Diamonds FC, Chester City and Macclesfield Town have all dissolved. Macclesfield Town, a club that existed for 146 years, were forced into liquidation due to debts in excess of £500,000. The amount of money that these four clubs owed at the point of disbanding is less than half of what Derby currently owe.

Under the stewardship of Mel Morris, Derby gambled – as many clubs have, and will continue to do so – on gaining promotion to the Premier League. While Forest and countless other teams were forced into selling their best players to ensure they adhered to Financial Fair Play regulations. It is reported that Derby’s operating costs by the end of the 2018-19 season were almost £1 million a week. During this time, they used every conceivable form of accounting trickery that they could to get around this. Mel Morris purchased the ground and then leased it back to the club for no fee, whilst assets and transfer fees were creatively recorded in the accounts. That’s not sour grapes on my part as a Forest fan, either. An independent enquiry into Derby County’s accounts found that there were discrepancies over the value of their players between 2016 and 2018, which broke EPL rules and for which they received a fine at the beginning of the 2021-22 season. All the time they were breaking these rules, they continued to invest heavily in the squad; Frank Lampard made numerous loan signings during his time as manager as well as spending £18.5 million on transfer fees. They even made high profile signings such as Ashley Cole and Wayne Rooney. Promotion, though, remained elusive and eventually, as it does for everyone, time ran out and the Rams were forced to pay the piper. Derby County entered administration at the beginning of the 2021-22 season and were additionally hit with a massive twenty-one-point deduction.

It is at this point in the story that I start to lose what little faith I had in the EFL. The history of our sport is littered with tales of clubs that gambled and ultimately lost. In every case, once the club is forced to face up to their financial situation and to balance their books, the playing staff are sold – usually at less than their market value – with a sense of desperation and recognition that these sales are going to negatively impact the ability of the team to compete, and almost always resulting in relegation. My own team have faced these very issues at various times since the turn of the millennium. Within three months of Paul Hart becoming first team manager of Forest in 2002, he was forced to transfer list every player in the squad to balance his books. Forest were then relegated to League One at the end of the 2004-05 season. And still, the club haven’t really recovered from the financial issues that derailed them.

Whilst Wayne Rooney might argue that some clubs have taken advantage of the situation at Derby to sign players below their market value, the club have not been forced into a fire sale of their assets unlike every other club who have ever entered administration. Reportedly, Derby have a yearly wage bill of £12.1 million. The transfer value of their highest weekly earner, Tom Lawrence, is approximately £4.5 million and his contract is set to expire at the end of the season. Despite interest from Bournemouth and QPR in the January window, the administrators simply refused to sell him. If the sale of Tom Lawrence had been approved, Derby would have saved themselves over £500,000 in wages as well as being able to use the money from his transfer fee to repay some of their debts. Instead, they were allowed to simply state that he would not be sold. An interesting move given that the EFL had formerly expressed their grave concern that the club did not have the money to complete the season.

Selling Lawrence would have undoubtedly impacted Derby’s chances of avoiding relegation and I can understand why they did not wish to sell him, but that shouldn’t even be a consideration. During the same period that Derby were employing a creative writing approach to their accounting, Forest were selling one of our best players, almost every season, to ensure that we stayed within the rules of FFP. I have no doubt that if you were to ask fans of any team across the footballing leagues, they would tell a similar story. Derby still appear to be under no pressure to pay their dues, feeling almost as if they are able to do what they wish regarding selling players and refusing to shift big-wage players. Despite the FA stating that Derby needed to start balancing the books by the beginning of February, their deadline was moved to March. Why? Well, that is anyone’s guess.

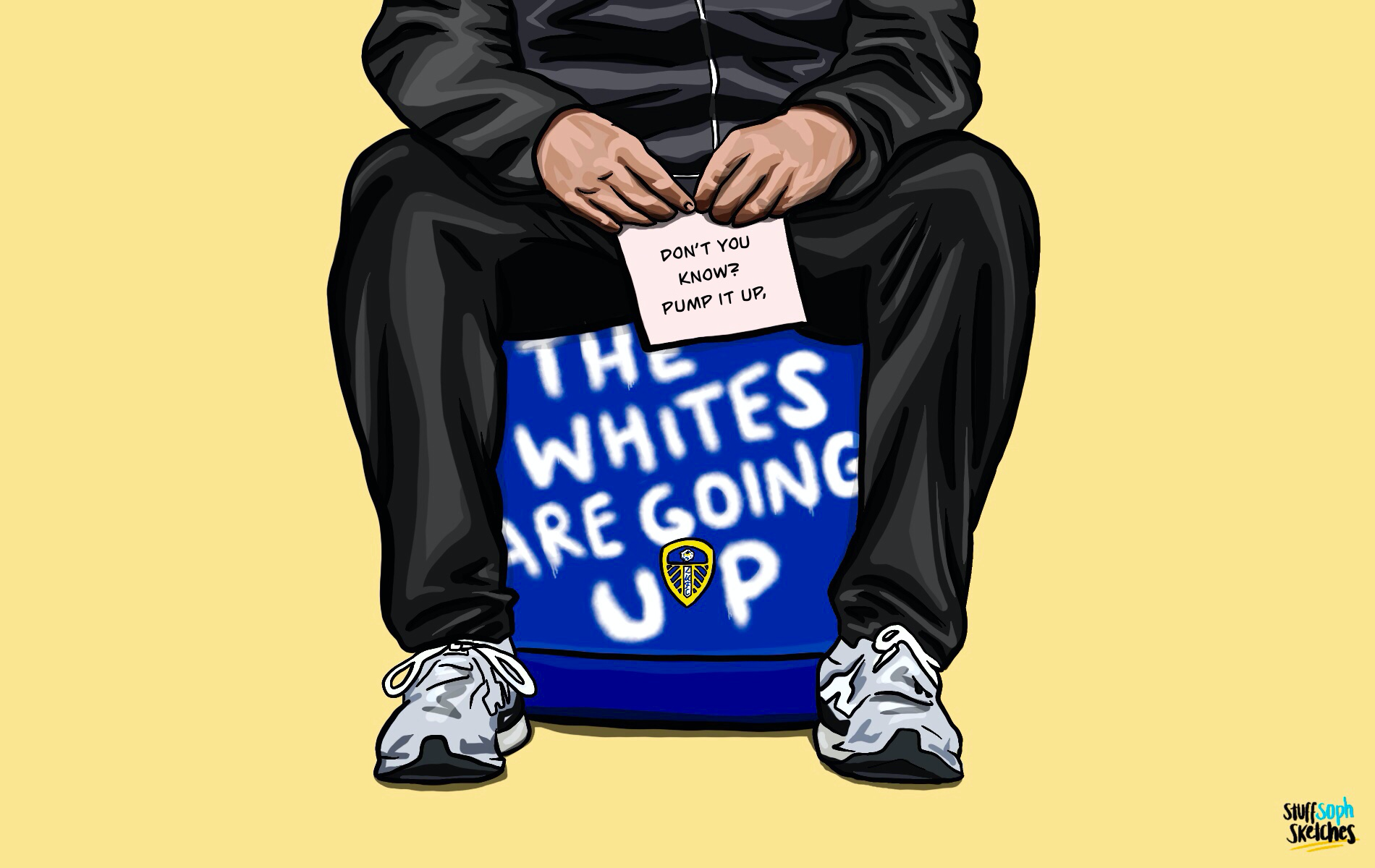

I can only imagine that Leeds United wish they had employed a similar approach, or at least the same administrators, when they were in their own dire financial straits in the early to mid-2000s. Their debt peaked at approximately £119 million and, when they were unable to make repayments, many exciting players had to be sold. Peter Risdale, the Chairman in the late 1990s and early 2000s, had gambled on Leeds being in the Champions League and the financial windfall that this would bring. Ultimately, their decline began when the club failed to reach European qualification at the end of the 2001-02 season. As a result, Leeds attempted to sell all their prized assets but couldn’t avoid the inevitable as their policy of high wages and large transfer fees quickly caught up with them. Despite selling Rio Ferdinand, Robbie Keane, Robbie Fowler and numerous others, the club were relegated in 2004. Just one day later, Alan Smith (lifelong Leeds supporter) was sold to Manchester United for £7 million in an act seen by some as the greatest act of treachery. It later emerged that the club could not afford to pay his wages and it was only through his sale to Manchester United that the club could avoid administration. Manchester United paid the full fee at the time of the transfer, rather than in instalments, and Smith even wavered his percentage to help ensure that Leeds had a chance at survival. Unfortunately, Smith’s transfer (and the fire sale before him) proved to be in vain as Leeds entered into administration at the end of the 2006-07 season, an action that confirmed their relegation to League One. Now, if Derby County’s approach is anything to go by, Leeds would have been better off ignoring the financial realities of their situation and simply carrying on.

Nevertheless, Derby’s financial position is nothing in comparison to that of Spanish giants FC Barcelona. With operating debts of approximately £1.2 billion, the club has been forced into restructuring player contracts so that they can register new recruits. Yep, that’s right, despite being more than a billion pounds in debt, the club are still allowed to sign new players. Barça have just spent around £52 million on Ferran Torres, taking home £202,000 per week; they have signed Pierre-Emerick Aubameyang on a free transfer, with a weekly wage of £100,000; they have confirmed the loan signing of Adama Traoré on £15,000 per week and completed the free transfer of Dani Alves for £1,000 per week. In the grand scheme of elite European football, these are not huge sums of money by any stretch of the imagination, however, when you consider the likes of Macclesfield Town it is a different story. After a legacy of 146 years, remember that Macclesfield were forced into liquidation because of debts in excess of £500,000 – what Aubameyang will earn in just over a month. After the first five months of his contract (worth £2.1 million), his wages will again increase. It doesn’t seem outlandish to suggest that when you owe over a billion pounds (a near ninety-six times more than the amount that put the nail in the coffin for the likes of Bury), you just shouldn’t be allowed to spend any more money.

It is not fair to state that all teams will be subject to Financial Fair Play regulations and then not enforce the rules consistently. Mansfield Town, Bury Town, Chester City and Dagenham & Redbridge did not need to go out of existence. If their stature in the global game were the same stakes as Barcelona or Derby County, they would have been allowed to continue to run at a loss. That’s what this is really about. Barça know they will not be allowed to go under, so they don’t really need to adhere to Financial Fair Play. Derby are media darlings – Frank Lampard managed them and now Wayne Rooney’s in charge, for God’s sake – we can’t possibly allow them to go bankrupt! So why is it that the others could? They all had a loyal fan base, employed numerous people and, to greater or lesser extent, represented their local community. They deserve to exist just as much as Derby and Barcelona. They might not have as many trophies, generate as much money or be in the wider footballing world’s consciousness as much as other teams, but they are still football clubs after all.

With all the money that football now generates, why can’t there be a fund created by UEFA to ensure that all teams can be supported should they require it? If Derby’s administrators don’t have to fire sale their players, why isn’t there a rule created making this fair for all sides in similar situations? Why as football fans, do we not do more to support the teams that are struggling? Football exists in its current guise because of us, football belongs to the fans and supporters – not to UEFA, national FA’s, agents, or television companies. I am not naïve, money will always be involved in the game, rich teams will always be able to sign the best players, poorer teams will always have to sell their prized assets to balance the books. All I am asking for is for some fairness and equality in the how rules are applied. No football club needs to go bankrupt with the astronomical financial figures involved in the game today, but that fact shouldn’t be the privilege of the few clubs that the footballing authorities deem it applicable.

There are many teams that could have been mentioned who have benefitted from or been penalised by the inconsistent application of financial rules. It is not intended to suggest that any team is holier than another. I have no doubt that my own team, Nottingham Forest, could very easily find themselves in a spot of bother once more. Yet, if Manchester United ended up in a dire financial situation, I’m sure people would be rushing in to save them. I just hope that whichever club falls foul of Financial Fair Play next is not forced out of existence.