A Long Read (23 minutes)

Just after 5pm on the 4 May 1949, a small Fiat aircraft carrying thirty-one people from Lisbon, via Barcelona, crashed into the side of the Basilica of Superga in Turin, Italy. The monks inside the chapel, when feeling the walls vibrate and hearing the crash, were first to the scene. Rushing outside, they were greeted by carnage with burnt and mutilated bodies strewn amongst the wreckage; the plane was destroyed, and no passengers survived. Most of the bodies were so badly burnt that identification was only possible when searching for documents and personal belongings. Monks and rescuers had no idea who had been aboard the plane until they opened one of the suitcases, untouched by the crash, and discovered a football kit of burgundy shirts with the tricolour shield.

To date, only three teams have won five consecutive Serie A titles, the first being Juventus in the years 1931-1935 and 2012 to the present. Internazionale also succeeded in doing so from 2006 to 2010 (despite finishing fifteen points behind first place, they were awarded the title in 2006 as Juventus were stripped of the trophy and relegated as a result of the Calcipoli Scandal). But perhaps the greatest team of them all was the Grande Torino side of the 1940s. Unlike Inter and their Turin neighbours, the Torino side that had dominated Italian football throughout the 1940s were robbed of the opportunity to compete for their sixth Scudetto. The plane that crashed into the side of Superga, killing everyone on board, consisted of eighteen Torino players. The fatalities included the entire first team squad (except Sauro Toma, who luckily missed the trip through injury), two club directors and three members of their backroom staff. The first team coach and Englishman Leslie Lievesley, and his supporting technical coach Egri Erbstein were among those found dead. In truth, the Superga plane crash is a tragedy from which, Torino Calcio never fully recovered.

Larger clubs circled Torino’s squad like sharks and, with the prospect of earning more money playing elsewhere, Novo and Erbstein were facing increased difficulties keeping the team together and maintaining Torino’s place atop of the Italian footballing tree.

Prior to their achievements in the 1940s, Torino had only won the Scudetto once in 1928. They actually won the league a year earlier, but had it revoked due to their involvement in the Allemandi Case (a match fixing scandal that rocked the sport in Italy). After winning the league in 1928, thanks to the goals of the Trio delle Meraviglie (Trio of Wonders) – Julio Libonatti, Adolfo Baloncieri and Gino Rossetti – Torino failed to build on their success and fell into a period of decline as the club made a series of poor management decisions both on and off the field. Although they did enjoy some success, winning the Coppa Italia in 1936. After their title victory in 1928 however, the fans had to watch their cross-city rivals go from strength to strength with Juventus winning five consecutive Serie A titles while Torino endured mediocre performances.

Every great team or club requires a catalyst: Real Madrid’s capture of Alfredo Di Stéfano; Manchester United appointing Sir Alex Ferguson; Pep Guardiola at Barcelona; Napoli signing Diego Maradona; the list is endless. Torino’s stimulus was not a player or manager but lifelong fan Ferruccio Novo, becoming President of the club. Incidentally, Novo had signed for his boyhood club in 1913 as a youth player but was not good enough to progress much further; ‘I was a duffer’ he reported once, smiling. Not making the grade as a player, Novo instead focused on becoming the most important person at the club, undertaking various roles at the club before ascending to the presidency. After fulfilling his life goal, Novo very quickly made it clear that the management of the club would revolve around himself and a small number of carefully hand-picked board members. He began by reorganising the club, surrounding himself with trusted and loyal advisors. Shortly after, Novo appointed Ernö Egri Erbstein as coach of the first team and began moving towards the English model of club management.

Of all the decisions that Novo made as President of Torino Calcio, the appointment of Erbstein was perhaps the most important. Despite producing incredible results with Lucchese, taking them from Serie C to midtable in Serie A in four years, Erbstein, as a Hungarian Jew, had been released by the club due to the pervasive anti-Semitic sentiment in Fascist Italy in 1938. Turin was predominately anti-fascist, and the racial laws of 1938 that chased Erbstein out of Lucchese remained largely unpopular. Novo, driven by a desire to create a working philosophy that ran throughout his club, wasted no time in appointing Erbstein. The President sought a similar top-to-bottom organisation that had underpinned Herbert Chapman’s successful Arsenal side. Whilst his role at the club was a little unclear, Erbstein influenced the club almost instantly. Erbstein himself described his role as ‘something more, and at the same time something less, than manager of Torino’. Such was the strength of his relationship with Novo that after being forced to return to Hungary during the Second World War, Erbstein remained in regular contact with the President and secretly travelled to Italy on several occasions to discuss the team and undertake scouting missions.

However, the Torino faithful’s initial impression of Erbstein was not entirely positive. Whilst he wasted no time in making an impression on the first team squad, signing Walter Petron (nicknamed “the little butterfly”) from Padova, Giovanni Gaddoni from Serie C side Piacenza and Aldo Olivieri from his former employers Lucchese. Only Olivieri, the “Magic Cat”, was considered a good signing with the captures of Petron and Gaddoni being questioned by the naysayers. Erbstein’s side were whistled off the pitch at half time in a pre-season friendly against the reigning champions, Ambrosiana-Inter. They recovered and managed to draw the match, but it was clear that the expectations at Torino were much greater than at any of Erbstein’s former clubs…not that he needed to be concerned.

Torino won their first league fixture under Erbstein’s management against Triestina 1-0, with Olivieri (who Erbstein had sent to dancing lessons to improve his agility and poise when managing at Lucchese) saving two penalties. Their next league fixture was away at Livorno where they managed a 1-1 draw, but it was in the third league fixture against Lucchese that Erbstein’s Torino demonstrated what they were capable of. Despite conceding a goal in the first minute and being reduced to ten men, Torino hammered Lucchese 5-1, Petron proving his doubters wrong with a virtuoso performance. The next league fixture saw Torino travel to Bologna, the pre-season favourites for the title, for a match in which the press felt would show up Torino’s shortcomings. Instead, Torino demonstrated their title credentials defeating the Rossoblu 3-0. They went on to lose only once in the first ten games and were joint top with Bologna on 27 November 1938. Within a week, however, Erbstein was forced out of the club as a result of the anti-Semitic race laws. Without Erbstein at the helm, Torino fell away in the 1938-39 race for the Scudetto, finishing second and four points behind Bologna as the eventual winners.

After falling away in the 1938-39 season, Novo recognised that he needed to make changes and strengthen the squad. Whilst Torino did not challenge for the title in either the 1939-40 or 1940-41 seasons (Italian football continued throughout the first years of the Second World War and was not suspended until 1943), Novo demonstrated his skill in recruiting players that would help establish Torino as a footballing force in both in the immediate and post-war future. Franco Ossola, an eighteen-year-old winger was signed from Varese for 55,000 Italian Lire in 1939. Before the 1941-42 season, Novo purchased another winger, Romeo Menti, from Fiorentina as well as Aldefo Bodoria, Felice Borel and Gugliemo Gabetto from Juventus. Gabetto was signed upon the recommendation of Borel as Juventus were planning to sell him to Genoa for 300,00 lire, but Torino could sign him if they upped the offer. Gabetto was signed for 330,000 lire and along with Bodoria, the goalkeeper with huge hands, the pair would become the only two players to date who have won the Scudetto with both Juventus and Torino.

Borel’s influence didn’t stop at making transfer suggestions either. Having been impressed at the effectiveness of the WM formation used by England during a friendly against Italy in 1939, Borel advocated changing Torino’s formation to follow the English model. Borel’s enthusiastic support of the WM was enough to convince Roberto Copernico, a member of Novo’s trusted board, that the formation would have far reaching consequences for Torino Calcio and Italian football as a whole.

Convinced that they had the personnel to be successful playing the WM system, Novo and his underlings decided to change Torino’s formation. The new formation was given its first outing in a 1-1 draw with Genoa on 21 December 1941 and successfully implemented for the remainder of the season, proving instrumental in helping Torino finish second to Roma who won the league by just three points. Impressed with his foresight and despite only being twenty-eight years old, Novo offered Borel a five-year contract to be player-manager of Torino. Borel declined, instead returning to Juventus after just one season with Torino. Borel’s decision was influenced by the fact that he wished to possess the far-reaching powers that Novo had entrusted Erbstein with – a man who, although he was no longer physically at the club, was always present.

Novo softened the blow of losing Borel by breaking the transfer record in July 1942 when he paid Venezia 1, 250, 000 lire, plus two players, to sign Valentino Mazzola and Ezio Loik. Mazzola and Loik had been instrumental in helping Venezia win the Coppa Italia in 1941 (their only major trophy to date) and more importantly, had inspired Venezia to a 3-1 victory over Torino, which ensured that Torino finished runners up to Roma that season. Rumour has it, that after this defeat, Novo walked into the Venezia changing room and struck the deal that would see both Loik and Mazzola represent Torino the following season. The transfer raised eyebrows all over Italy, not least at Juventus who had a verbal agreement with Venezia to sign both players. Considering the average daily wage for a factory worker in Italy at the time was fifteen lire, the fee for the two players was astronomical. Some argued that you could build an entire squad for the amount Torino had paid for the pair, but Novo was unmoved, convinced that he had signed the players who would be the missing link in his master plan.

Novo was proven right as Torino became the first team in Italy to win the double. In a close-fought battle for the title, Torino won their second ever Scudetto on the final day of the season, defeating Bari 1-0, winning the league by a point ahead of second place Livorno as a bit of a surprise package. Persuaded by the Italian national coach Vittorio Pozzo, Novo had abandoned the WM system for the start of the 1942-43 campaign with disastrous results, losing first to Ambrosiana Inter 1-0 and then Livorno 2-1. His star signings of Loik and Mazzola played poorly in the defeat to Ambrosiana and were blamed for the defeat. Torino’s next fixture was against their local rival Juventus and unwilling to contemplate losing the derby, Novo reintroduced the WM system. Torino won 5-2 with Mazzola scoring his first league goal for the club. The WM remained, and Torino went from strength to strength, banishing the demons from the year before by defeating Venezia 4-0 in the Coppa Italia final, two weeks after clinching the Scudetto. Torino ended the season with the meanest defence and were second highest goal scorers, suggesting greater things were to come the following season. However, as the Second World War raged on, and despite the Italian FA’s best efforts, football was officially suspended after the 1942-43 season.

An armistice signed in September 1943 saw the country divided into two and the threat of air raids made it difficult for clubs to move around the country, resulting in Serie A being suspended. However, a reginal war tournament Alta Italia was created. Novo worked relentlessly to keep his squad together. While some clubs moved to different cities, Novo changed the name of the club to Torino Fiat for this competition. Playing under the guise of a team of factory workers, Novo was able to ensure that his players avoided being called to arms by getting them work permits, stating that they were employed by Fiat.

The Alta Italia competition was divided into three rounds and, conceived as a distraction to the war, was open to all teams regardless of standard. Due to the air raids, the tournament had no set venues or fixture lists and teams were further weakened with many players being called up for military service. Despite the difficulties, the tournament was concluded on 16 July 1944 in Milan, where Torino ended runners up to VF Spezia. VF Spezia – a team of firemen – defeated Torino 2-1 after Novo misjudged the ability of the Spezia side and agreed to play them only days after his squad had returned from a regional representative fixture. Novo was proven wrong after stating that Torino should easily defeat a weaker team regardless of how much rest they had. Spezia successfully implemented a new tactic that would later become known as the libero (or sweeper in English) which nullified and confused the great Torino team.

With the war coming to an end in 1944, a regional tournament was organised in which a match between Torino and Juventus resulted in a surprising reaction from the spectators. The war had not yet ended, and Italy remained a politically volatile country. In attendance were a large number of military personnel on leave or attending the football to take their mind off the fighting. Borel, who was once again playing for the la Vecchia Signora, put in a strong challenge on the Torino captain Mazzola. Enraged by the challenge, Mazzola jumped to his feet and threw all of his weight behind a punch. Borel avoided the blow and, such was the force behind the attempted punch, Mazzola again ended up on the floor. Whilst such an incident recounted almost seventy-five years after the event sounds comical, the Torino and Juventus players did not find it funny, and the incident sparked a mass-brawl which included the reserves of both teams. The brawl was broken up by the sound of a gunshot as a spectator fired into the air. In the resulting panic, several more shots were fired around the stadium as the players of both teams fell to the ground. Incredibly, calm was restored, and the game restarted as the players came to realise that their petty squabbles paled into insignificance when compared to the life and death situations that many in the crowd had endured.

Serie A returned for the 1945-46 season, albeit in a slightly new guise. The disruption and communication issues caused by the war had not yet fully been repaired or re-established and so it was decided that the tournament would be divided into two geographical leagues – the Northern Italy Serie A Championship (of which Torino would compete) and the Central-Southern Italy Serie A/B Championship. The top four teams from both leagues would then challenge for the championship in a final league stage. Novo had further strengthened his Torino squad before the season began. Erbstein had still not returned to the club, and so Novo appointed Luigi Ferrero as Head Coach. He also brought in goalkeeper Valerio Bacigalupo from Savona, full-backs Aldo Ballarin from Triestina, Virgilio Maroso from Alessandria and Marion Rigamonti and Eusebio Castigliano from Bresica. The Grande Torino team that would go on to dominate Italian football was almost complete.

By the start of the 1945-46 season Torino were fully committed to the WM system. Having decided to move away from the traditional 2-3-5 formation, the WM formation is perhaps best understood today as a 3-2-2-3 formation. In defence the three lined up with what we would understand as two fullbacks and one central defender. In front of the defence were two defensive midfielders and then in front of them, two attacking midfielders. The width was offered by two wingers and then a centre forward completed the outfield ten.

In goal was the fiery Bacigalupo, who overcame the disappointment of losing his debut to local rivals Juventus 2-1 to go on to make 137 appearances between 1945 and 1949. Ever the perfectionist, Bacigalupo was seen crying at training when he lost his place in the side after suffering a shoulder injury in the 1946-47 season. Bacigalupo’s response was to work even harder. His resilience and determination were rewarded first of all when he regained the number one spot at Torino and later in December 1947, when he made his debut for Italy in a 3-1 victory over Czechoslovakia.

The fullbacks of Maroso and Ballarin also made their debuts alongside Bacigalupo in the 2-1 defeat to Juventus on 14 October 1945. Maroso was known as “The Kid” and was noted by those who saw him play as the forerunner of the great Internazionale fullback Giacinto Facchetti. Maroso’s popularity and reputation were second to only Mazzola in the Grande Torino team; his forward running and desire to play out from the back was applauded by all that saw him play. Ballarin, the right-back was far more understated but just as important. He formed a great understanding with the more forward-thinking Maroso. Novo paid a contemporary record fee of 1,500,000 lire to complete the signing of Ballarin. Despite differences over the nature of his role, Ballarin proved more than worth the outlay, going on to represent Torino 148 times in four years as well as being a regular for Italy between 1947-1949.

Mario Rigamonti completed the back three. Away from football, Rigamonti enjoyed nothing more than escaping on his motorcycle, often rocking up to Serie A matches just minutes before kick-off. However, when he took to the field, centre forwards were left in no doubt as to the punishment they would have to endure in their attempts to score against him. Rigamonti took every goal scored against him as a personal insult and became the first in a long and illustrious list of man-marking Italian centre-halves. Amadei, centre-forward and international teammate, once reported that so bad was the physical fight between himself and Rigamonti that the day after the game he could not get out of bed. Other teammates reported that he defended like two men, allowing the rest of the team the freedom to dominate teams.

Infront of Bacigalupo and the back three were the midfield four collectively known as Quadrilatero. Giuseppe Grezar was the deepest lying of the midfield four, and despite being underappreciated by the fans, his immense contribution was appreciated by all that played alongside him. Hard tackling and strong, Grezar perfected doing the simple things when others would over-complicate. Scouting Grezar while he was at Triestina was supposedly what brought Erbstein back to Italy during the war. Grezar worked in tandem with Eusebio Castigliano, who made his debut on 14 October 1945 in the 2-1 defeat to Juventus. Castigliano’s role, similarly to Loik’s, was to turn defence into attack at every opportunity. After winning the ball, Castigliano would either drive into space or move forward with a number of quick passes. Nicknamed gamba di velluto (velvet leg), Castigliano was an elegant player with fantastic dribbling skills. However, Castigliano was not afraid to impose himself on a game more physically if required, defending doggedly, and using his significant physical attributes to win the ball back.

In front of Castigliano and Grezar were the double act of Loik and Mazzola, signed from Venezia in 1942. Loik and Mazzola’s game complimented each other perfectly. While Mazzola was considered the conductor, Loik was the engine of the team. Journalist Aldo Bardelli described Loik as ‘an enlightened workhorse’, and it was Loik’s box-to-box running that linked the W and M in the Torino system. Loik was more than a simple workhorse, and although he was not blessed with the natural skills of Mazzola, he demonstrated great technical ability with a high goal scoring rate for a catagoric “team player” scoring seventy-two goals in 181 appearances for the Grande Torino team.

Mazzola was the superstar of the Torino team, demanding perfection from himself and all those around him. It was Mazzola who would roll up his sleeves to mark the quatro d’ora granta (the maroon quarter-hour), driving his team forward when he felt that the standard was dropping or that the team needed an extra-push. The former Juventus centre-half, Carlos Parola remarked that ‘when Valentino Mazzola was unleashed, he dragged literally the whole squad with him’. Athletic, two footed, good in the air and a powerful runner, Mazzola was afforded a free role in the Torino side, picking the ball up from defence in one moment before bursting into the box and attacking crosses only moments later. On the 20 April 1946, Mazzola scored the fastest ever hattrick in Italian football when he scored three goals in three minutes against Vicenza.

On the wings for Torino were Franco Ossola and Romeo Menti. Ossola, two-footed with great ball control and a powerful shot, played on the left with the pacey and powerful Menti on the right. Menti’s game was based on simplicity, using his pace to go past defenders. Being two footed, he was always calculating the best place to move the ball. Ossola was far keener on keeping the ball at his feet, taking on defenders and demonstrating his skilful dribbling. Both contributed their fair share of goals with Menti scoring fifty-three in 133 appearances and Ossola ninety-one goals in 182 appearances.

Upfront was the centre forward Guglielmo Gabetto, who was also signed on Borel’s advice. Allowed to leave Juventus, who incorrectly believed that his career was on the slide, Gabetto was rejuvenated at Torino where he became an integral part of the Grande Torino side. Linking well with Ossola in particular, the striker scored 125 goals in 225 appearances for Torino. Yet, there was more to his game than simply scoring goals. If defenders gave him space then he was the perfect foil for Mazzola, Loik, Ossola and Menti, dropping deeper to create room for their overlapping runs. But if defences attempted to mark him tightly, he was even more deadly – winning aerial battles, out-muscling his marker, and attacking crosses with acrobatic finishes.

Despite losing their first game of the 1945-46 season 1-0 to Juventus, Torino demonstrated their title credentials in their next two fixtures, defeating Sampierdarenese 6-0 and Genoa 5-0. Torino would go on to win the Northern Italy Serie A Championship, scoring sixty-five goals and conceding only eighteen in twenty-six games. Other notable victories included defeating Milan 4-0 and avenging their opening defeat to Juventus, winning the return fixture 1-0. But it was in the final league stage that Torino demonstrated their dominance over all other Italian teams, and which marked the birth of Grande Torino. Facing Roma away from home, Torino scored six goals in twenty minutes (all of which came in the first half) and such was their dominance that Head Coach Ferrero told the players to ease off in the second half to avoid humiliating their hosts. Torino would score one more to complete a 7-0 victory and when Mazzola was forced from the field due to injury, the entire stadium rose to applaud him off. Another loss and a victory over Juventus as well as thrashing Napoli 7-1, meant that the league title was to be decided on the final day of the season. Juventus travelled to Naples and Torino played at home against Pro Livorno. Whilst Juventus could only manage a draw with Napoli on 28 July 1946, Torino hammered Pro Livorno 9-1 to emphatically seal the Serie A title at the Stadio Fildelfia.

Torino strengthened their squad further for the 1946-47 season with the return of Erbstein in September 1946, who was welcomed back with open arms by Novo as President. Many argued that the Head Coaches who were appointed since Erbstein’s removal in 1938 were simply warming his seat until he could return at a later date. Erbstein was returning to a championship winning team and a Head Coach who was not keen to relinquish the reigns of the first team. When Erbstein returned in a position understood today as Technical Director, he worked alongside Ferrero, the first team coach, rather than replacing him.

It was clear that Erbstein was simply happy to return to his spiritual home and work for his friend Novo again. Having somehow survived the war, Erbstein escaped a Nazi labour camp and his daughters evaded capture from a convent which neighboured an SS regiment (it is worth reading Dominic Bliss’ fantastic biography of this footballing genius). Erbstein never forgot what his friends had done for him during the war, explaining a couple of years after his return to Torino that ‘Novo was among the very few people, if not the only one, who… not only did not abandon me but also proved to be a true friend, allowing me to make my existence certainly better than it was’. Despite the fascist anti-Semitic laws, Novo remained in contact with his friend throughout the war. Interceding on Erbstein and his family’s behalf when he was arrested by the Nazis in 1938, Novo helped secure their release from the house in which they were imprisoned. When Erbstein enquired later what had happened to the other families sheltered in the house, he was informed that they had all been executed. Novo’s intervention had saved their lives. Erbstein, who had set up a textile business with his brother during the war years, was further supported by Novo who used his connections to ensure enough business for Erbstein’s latest venture.

With Erbstein back where he belonged and working alongside Ferrero, Torino rose to dominance seldom seen in competitive sport, showcasing a style of football that was loved and appreciated not only by the Torino faithful, but also throughout Italy. Disappointed by the defeats suffered at the end of the 1945-46 season, Erbstein set about making the Torino team more defensively compact out of possession and with a greater focus on faster off-the-ball movement when in possession. However, the initial results were unimpressive. Torino won only one of their first four league fixtures as the side struggled to come to terms with this new style. The turning point came in their fifth league fixture against Juventus which (despite ending in a goalless stalemate) proved to be the catalyst for Grande Torino as they proceeded to win their next ten league fixtures, including an impressive 4-0 victory over Bologna in November. Bologna were the early pace setters in the league, holding a four-point advantage over Torino. Their goalkeeper had not conceded a goal since the opening game of the season and the importance of the fixture was not lost on the Torino faithful. Torino responded by destroying Bologna and sending a clear message to the rest of the league that they were not going to give up their title without a fight.

Torino would only lose three times in the 1946-47 season, scoring 104 goals as they won the league by an impressive ten points (it was 2 points for a victory back then). Mazzola, playing as what can be considered an attacking midfield position, was the league’s top goal scorer with twenty-nine goals, eight more than Milan’s Ettore Puricelli – the second highest goal scorer. Torino had now become the benchmark for Italian football and the club to emulate both on and off the field.

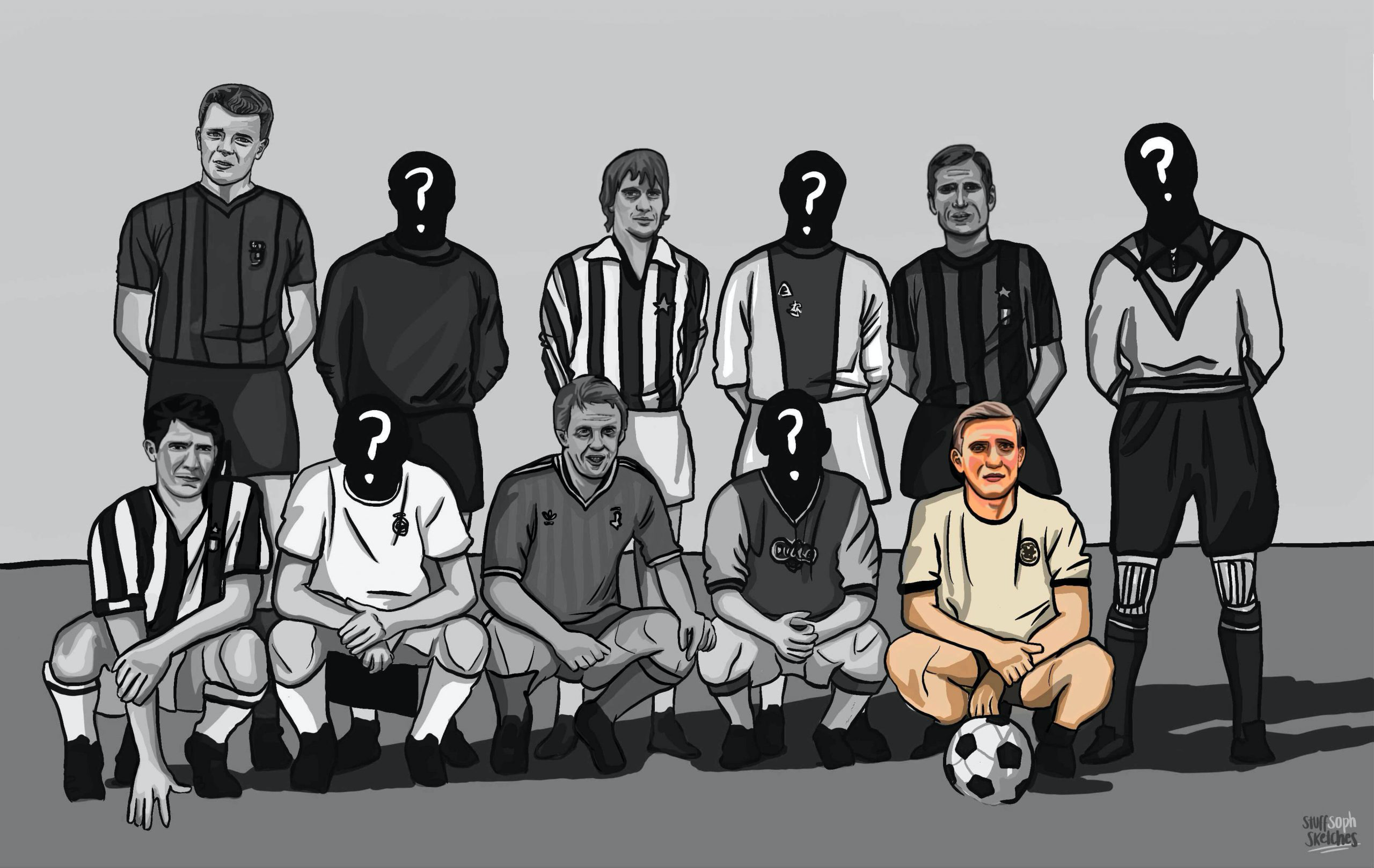

Torino’s dominance of Italian football was reflected in the international fixture between Italy and Hungary on 11 May 1947, when only the goalkeeper Bacigalupo was not selected in the starting line-up. Ten players from one domestic side being selected for an international team even set a World Record, not that the Italian’s were surprised. Torino’s brilliance was so obvious that it was simply considered a formality; it would be being more surprising had the selection not featured so many faces from the hugely successful Torino side. Italy went on to defeat Hungary 3-2 with Gabetto scoring two goals and Loik with a last-minute winner. In essence, Grande Torino had defeated a similarly talented Hungarian team.

The 1947-48 season was even more impressive as Torino won their fourth consecutive Scudetto, scoring 125 goals and conceding only thirty-three. Torino set records for the highest points advantage over second place (sixteen points), largest Serie A victory (10-0 vs Alessandria), highest number of wins from a forty-match season (twenty-nine wins), longest unbeaten streak (also twenty-nine games) and the greatest number of home wins with twenty. However, the larger clubs circled Torino’s squad like sharks and, with the prospect of earning more money playing elsewhere, Novo and Erbstein were facing increased difficulties keeping the team together and maintaining Torino’s place atop of the Italian footballing tree. As always, Novo and Erbstein’s approach was ahead of its time; creating good working relationships with smaller regional clubs, the pair hoped to twin Torino with these satellite clubs in a manner like the modern “feeder-club” systems seen in today’s game. Torino would receive first refusal on up-and-coming players, and, in return, the other clubs would receive management consultancy. Even Erbstein himself was loaned to Alessandria for the remainder of the season after their 10-0 drubbing at the hands of Torino and the odd Torino player who had fallen out of favour would also follow suit.

Unable to compete with the richer clubs financially, Torino were always looking for an advantage wherever they could find one. Whilst the rest of Serie A frowned upon the arrangement, the “feeder” arrangements with the smaller satellite clubs was a way of helping Torino ensure that they were able to compete with the wealthier Serie A sides. Under Erbstein’s direction, the club also invested to a greater extent in sport science. Delving into the nutrition of the players, Torino imported fruits and vegetables from the South and distributed vitamins to the players after Erbstein had researched the physical condition of players at various points of the season. Erbstein equally worked on the psychological aspect of the game, scribbling down inspirational quotes and slogans that he shared with the team. His personal notes and philosophy further demonstrated the importance of players being happy in what they did. Erbstein believed that being able to “play” created freedom in which players could take control of their own destinies and ultimately be successful, a model loosely based on the influential Dutch Philosopher Johan Huizinga’s theoretical approach.

Having secured the Scudetto in 1948 with relative ease, the 1948-49 season proved more challenging. Despite Erbstein being appointed the Head Coach role in the summer of 1948, the club were rocked by Mazzola declaring his desire to leave the club for Internazionale. Mazzola had been offered four times his salary by Milan and expressed his wish to join the Nerazzurri, but Novo refused to allow him to leave. Valentino Mazzola would never join Inter, but his son Sandro would enjoy a long and illustrious career with them becoming an integral part of Herrera’s Inter Milan team of the 1960s.

The successes of the Grande Torino team had been based on an evolving squad system. With an aging group of players, Novo and Erbstein wished to create a system in which the youngsters learned from seasoned champions before later replacing them. Pietro Operato, Dino Ballarin, Rubens Fadini, Julius Schubert, Ruggero Grava and Emile Bongiorni were all introduced to the squad to learn at the feet of the masters. Opportunities for youth players were scarce, but it was on the shoulders of the squad players that Novo and Erbstein were planning to continue their dominance of Serie A.

Despite Mazzola’s head being turned (quite understandably so) and Castigliano agreeing to join Inter for the following season, Torino were top of Serie A when they travelled to Milan to face second placed Internazionale. After battling to a goalless draw in Milan, Torino were four points clear with four games remaining and everyone within the club were left feeling that a fifth consecutive title was a formality. It was in such good spirits that the Torino squad made its way to Lisbon to play in a testimonial match for the Portuguese and Benfica captain Francisco Ferreira. Ferreira and Mazzola had become friends after Italy had defeated Portugal 4-1 in a friendly earlier in the season and Mazzola was instrumental in convincing Novo to allow the side to travel to Lisbon, although the season was yet to be concluded with four important league fixtures left to play.

On the 3 May 1949, the Grande Torino side played their last ever match, losing 4-3 to Ferreira’s Benfica. Ossola opened the scoring before Benfica equalised and then took the lead. The substitute Bongiorni equalised for Torino before Benfica scored twice more. In the final minutes of the game, Mazzola was upended in the box and Menti, the set-piece specialist, converted the resulting penalty to make the final score 4-3. In the end, the result didn’t matter; everyone in attendance had witnessed an entertaining match and Ferreira received the send-off that he deserved. As the players, fans and club representatives left the ground that evening, no one knew that they had witnessed the last of Grande Torino.

What caused the crash is still unclear. Supposedly, a dense fog had enveloped Turin perhaps causing the pilot to fly off course. Believing that he was entering the airport, he began his dissent too quickly and crashed into the eighteenth-century Basilica. On the 6 May 1949, 500,000 people lined the streets of Turin to watch the funeral procession, led by the Torino and Juventus youth teams in full kit, as Italy mourned on an unprecedented scale. Despite the fierce rivalry between the Turin clubs there was also great respect and Juventus, having seen their request to postpone their match on 6 May 1949 rejected by the league, instead boarded a later train to Palermo so they could attend the funeral.

Torino would win their fifth consecutive Serie A title in 1949, five points ahead of Inter, completing the season playing their reserve team in their final four fixtures with their opposition doing the same as a sign of respect. But the optimism created by Grande Torino was lost, the club would soon fall into years of midtable obscurity and relegation to Serie B as Novo and subsequent presidents attempted to replicate their talismanic team from the 1940s. The Filadelfia, the home at which Torino remained unbeaten for six years, was subsequently sold and the club have had to watch on as their neighbours have gone from strength to strength.

In post-war Italy, everyone welcomed il Grande Torino into their hearts. After years of political upheaval and a sense of shame regarding their involvement the Second World War, the Italian people turned to football to restore a sense of national pride. Grande Torino represented a sense of optimism for the future and, with the national side being near enough the same team but wearing blue rather than burgundy, there was a growing feeling that five years after Mussolini’s execution, Italian nationhood would be repaired should the Azzurri return from the World Cup in 1950 as World Champions once again. Sadly, it was not to be.

We will never know if Torino could have maintained their success, if Erbstein and Novo continued to weave their magic or if the richer clubs would have swooped upon Grande Torino and picked the team apart. Would Mazzola have engineered his move away from Turin? Would Castigliano have joined Inter in the summer of 1949? Or would Novo have achieved his desire of Mazzola ending his playing career with Torino? Maybe Mazzola’s son, Sandro, would have followed in his father’s footsteps and represented Il Toro rather than Inter Milan. Perhaps Juventus would still be chasing the record for most consecutive Serie A titles and wouldn’t be the biggest team in Italy. Unlike all other great teams, Grande Torino will never grow old, their achievements will never fade, but we as football fans are poorer for not having seen that happen. We will never know just how good they could have been. However, our loss as football supporters is insignificant when considering the loss of the families who would never see their loved ones again. After all, as beautiful as the sport is, it is just a game. Erbstein’s life is a reminder of just how fragile life can be; having survived Nazi persecution, he lost his life on a mountain in Turin. Torino’s greatest gift to us all was not the revolutionary football that they played but a reminder to live every day to the fullest.