Arguably the greatest German footballer to never win a cap for his country, Horst Blankenburg, while unfortunate enough to be playing libero at the same time as Franz Beckenbauer, was surely good enough to represent his country at least once. He would have been a fantastic option had he been selected, even if only as a squad player in major tournaments. Yet, he was continually over-looked by the German coach Helmut Schön, who frowned upon German players playing outside of the Bundesliga. Underappreciated by his national coach, and somewhat of a footballing nomad, Blankenburg felt most at home when playing for Ajax for five glorious years, where he enjoyed successes that would have won him international caps for any other national side. Although he ended his career away from Amsterdam, it is with the Dutch giants that he played his best football and was most appreciated.

Blankenburg started his professional career at 1. FC Nürnberg in 1967. Albeit a successful season for Nürnberg, who went on to win the Bundesliga title (which they have not won since), Blankenburg felt he had not significantly contributed to the team’s success. Having been involved in a motor car accident during preseason, thus starting the season injured, Blankenburg only made thirteen appearances – none of which were in the league. Feeling as though he had little input, Blankenburg made the first of many transfers in his career, moving to Wiener Sportklub in Austria, where he won a league runner-up medal in his only spell in the country. His performances impressed TSV 1860 München who paid 100,000 deutschmarks to bring Blankenburg back to Germany. Despite playing regularly, a personal improvement upon his first season in Germany, it was not a successful season for 1860 München who were relegated from the Bundesliga.

‘I’m Horst, I’m a Kraut and I’ve come to play football with you’.

In 1970, there was no second division like the 2. Bundesliga in German football nowadays, so when TSV 1860 München were relegated, Blankenburg started the season playing regional football. This, coupled with Blankenburg’s outspoken and rebellious run-ins with the club hierarchy, meant that when Ajax expressed an interest in taking the defender to Amsterdam all parties were happy for the transfer to proceed. On 14 December 1971, after Velibor Vasović had made it clear that he wished to leave Ajax and join PSG, Blankenburg was signed for 320,00 deutschmarks, a record transfer fee for TSV 1860 München at that time. When arriving at Ajax, Blankenburg introduced himself to his new teammates by plainly stating that ‘I’m Horst, I’m a Kraut and I’ve come to play football with you’. Simple as that.

Over the next three years, Blankenburg would win three European Cups (now the Champions League), two Eredivisie (Dutch League) titles, two European Super Cups, two KNVB (Dutch) Cups and an Intercontinental Cup. Becoming an integral part of the all-conquering total-footballing team, Blankenburg got the backing he needed from the Ajax managers – Rinus Michels and then Ştefan Kovács – enabling him to fulfil his potential.

Though it was Michels who brought the volatile defender to Ajax in the first place, it was the 1971-72 season, after he had left for Barcelona and in came Kovács, that Ajax were at their most fluid. Blankenburg had now replaced Vasović in the starting eleven, (he had retired from football due, in part, to health concerns rather than signing for PSG) and the gifted sweeper was given more freedom and encouragement to play his naturally skilful game – joining the attack, whenever possible, safe in the knowledge that someone would cover for him. Cruyff remarked that Blankenburg was much more of an attacking option than Vasović. Regarded as a sophisticated player by many, Blankenburg knew when to go forward and when to defend and whilst “Total Football” is synonymous with attacking flair, Blankenburg’s defending when called upon was up there with the best. Borussia Mönchengladbach’s head-coach at the time, Hennes Weisweiler, called him the “modern libero”. This forward-thinking flair combined with his defensive solidarity were just the foundations that Blankenburg required to impose himself on a game, yet, international recognition continued to allude him.

Blankenburg’s lack of international recognition is hard to understand; considered good enough to be selected for the European Select eleven and ironically coached by Helmut Schön (the German head coach), he remains the only player selected for such a team without first representing their country. Helmut Schön was certainly not keen on picking players who played outside of the Bundesliga. The mercurial Günter Netzer for example, despite helping Real Madrid to win two league titles and two Copa del Rey competitions, was only selected once at the World Cup of 1974. However, in Schön’s defence, his goalkeeper and back line were made up almost entirely of the Bayern Munich defence – the team that took Ajax’s crown as the pre-eminent side in European football in 1974. However, Blankenburg’s continued exclusion from the squad is suggestive of something far more personal in the decision-making process than simply where he played and who was available at the time. Blankenburg himself has surmised that perhaps he wasn’t selected because he was too outspoken or that Schön simply didn’t like him. Blankenburg’s remark to a journalist that ‘Schön can lick my arse!’ when discussing his relationship with the German coach probably didn’t help his cause either.

In 1973, Ajax and Blankenburg were on their way to a third successive European title, but on-route came up against Bayern Munich in the quarter finals. Undoubtedly motivated by a desire to show the German people what they were missing and against defenders that were keeping him out of the national team, Blankenburg played like a man possessed. Ajax’s 4-0 victory was so emphatic that Sepp Maier considered it the worst ever Bayern performance and Blankenburg’s show was so good that, for anyone who had watched the game, there was no question who had been the better libero in that fixture…and it wasn’t Beckenbauer.

The great Ajax team of the early 70s was dismantled after Cruyff and Neeskens left for Barcelona and, in 1975, Blankenburg returned to Germany when signing for Hamburg. Despite winning the DFB-Pokal (German Cup) in 1976 and the European Cup Winner’s Cup in 1977, Blankenburg struggled to settle at Hamburg; he missed the relaxed attitude of Ajax and the Dutch. The defender was soon on the move again, playing for Neuchâtel Xamex FCS in Switzerland, Chicago Sting (now disbanded) in the USA and KSC Hasselt (who merged with KSK Kermt in 2001) on loan in Belgium. He finally ended his professional career at SC Preuẞen Münster in Germany.

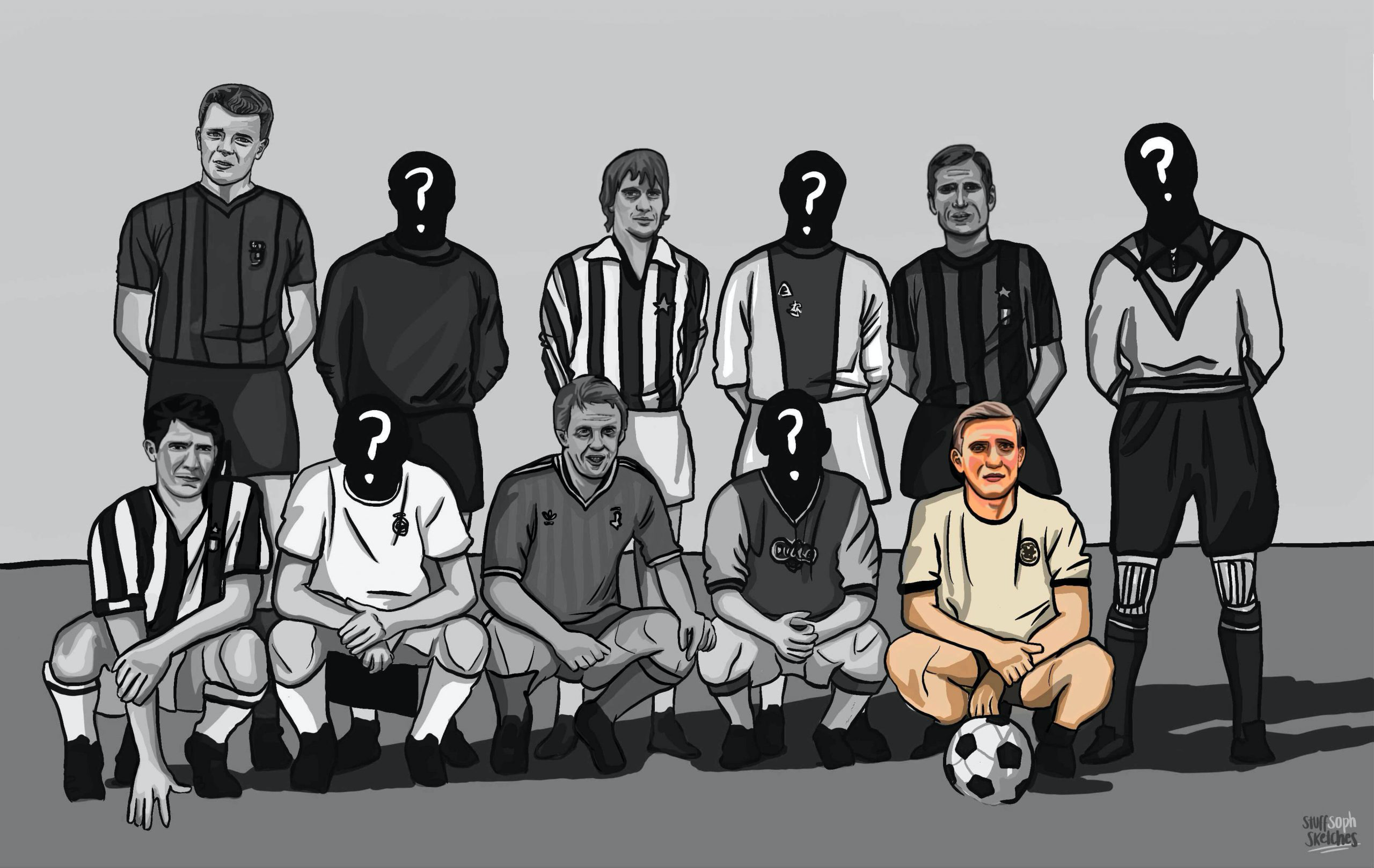

Seeing that he was ignored and overlooked in Germany, Johan Cruyff (who knew just a little about football…) once tried to convince Blankenburg to play for the Netherlands in the World Cup of 1974. Horst declined, continuing to hope that he would one day be called up for his national team. Considering the notoriously bad feelings between the German and the Dutch at the time, who knows how either country would have responded if a German defender had foiled the German attack and helped the Netherlands to win a world title. What seems less in doubt, is that if Blankenburg had declared for the Netherlands, he would have been selected in their starting eleven and would have strengthened the weakest aspect of their team. Would this have been enough to defeat Germany? We will never know, but it is worth noting that Blankenburg was the only non-Dutch player in the Ajax side that dominated European football throughout 1972 and 1973.

Blankenburg reflects that he is ‘content’ but ‘not happy’ with his footballing career, no doubt as a result his failure to represent his country. Unsurprisingly, Blankenburg always felt better treated by the Dutch, stating during Ajax’s centenary celebrations in 2000, that ‘the Dutch don’t forget what you do’. Indeed, they didn’t – naming one of the eleven bridges around Ajax’s old stadium in East Amsterdam after him, the ten other bridges were named after the other ten players who were involved in all three consecutive European Cup victories. Throughout the 1970s, it would be fair to say that Germany might have dominated world football even more so had Blankenburg been able to represent and impress his home nation.