Between April 1931 and December 1932, Austria’s Wunderteam went fourteen matches unbeaten and were arguably the greatest side in Europe. During this time, they won the Central European International Cup (the precursor to the European Championship), hammered Scotland 5-0, won 6-0 at home and 5-0 away to Germany, beat the Swiss 8-1, as well as defeating Hungary, Italy and Sweden. In December 1932, they became only the third team from overseas invited to play in England. The match took place at Chelsea’s Stamford Bridge and 42,000 fans crammed in to see one of the greatest ever football matches. If England had been paying any attention, instead of still living off their “we invented the game so we must be the best at it” reputation, then they would have foreseen the footballing education Hungary would teach them twenty-one years later. For, despite losing 4-3, it was the Austrian team’s style of football that really took the plaudits and inspired the great Hungary team of the 1950s. Austria’s best player was a slight, gaunt looking man nicknamed der Papierene (the paper man), Matthias Sindelar.

Born in 1903 in the Czech region of Moravia, Sindelar migrated with his family to Vienna in 1905 where he began his youth career for local side ASV Hertha Vienna some years later. In 1924, Hugo Meisl, Austria’s national manager and footballing pioneer, helped arrange for Sindelar to sign with FK Austria Vienna. Over the next two seasons, Sindelar helped his new team to win two Austrian Cups and only their second Austrian Championship in 1926. His performances led to him being selected for the Austrian national team in the same year. Despite scoring on his debut, a 2-1 victory over Czechoslovakia, as well as two goals in a 7-1 victory over Switzerland and a fourth goal in three games against Sweden, Sindelar fell out of favour with Austria’s disciplinarian coach. Having taken a chance in playing the slight-of-build Matthais Sindelar, Meisl returned to the strengths of traditional 1920s attacking play with Josef Uridil. If Sindelar was “the paper man”, then Uridil was the tank. For the most part of the 1920s, Sindelar was in the international wilderness, making only fleeting appearances and forced to watch on as Austria won only two out of seven international games before the visit of Scotland in May 1931.

Intelligent and athletic, almost balletic, the café writers and artists compared Sindelar’s fragile creativity to that of their own.

Although he was referred to as “the pre-war Pelé”, Johan Cruyff seems a better comparison to Sindelar’s skills. At a time when most footballers were big burly physical presences, Sindelar was unusual in that he was thin and bony in stature. Yet, Sindelar helped revolutionise the centre forward role, and in doing so, influenced the creation of the false nine position. Hugo Meisl’s brother, Willy Meisl was a sports journalist who praised Sindelar for he had ‘an inexhaustible repertoire of tricks and ideas’. In his book Tor! The Story of German Football (2002), Ulrich Hesse Lichtenberger wrote that the Austrian style of play was known as schieberl (‘ballet’, ‘grace’, and ‘slide’ are the closest English equivalents) and Sindelar was the embodiment of this; people wanted to see “the paper man” play as much as to learn how the game ought to be played. Other contemporaries even suggested that Matthais Sindelar had brains in his legs.

Café culture dominated Austria in the 1920s and 1930s with the intelligentsia meeting to discuss ideas and views on anything they considered worthy of their time. Football was one such subject and each team had its own club-based café where players, supporters, directors and writers could meet to discuss all things football. Weltam Montag, writing after the Second World War, described the culture as a kind of revolutionary parliament for the friends and fanatics of football. While each team had its own coffeehouse, the Ring café in particular became a social hub as the centre of the Austrian footballing community by 1930. In Sindelar, the Viennese café culture had a player that they considered their own at last; a player who embodied Austrian football, unlike anything that was played in Britain and Italy – a style based on guile, balance and brains. Intelligent and athletic, almost balletic, the café writers and artists compared Sindelar’s fragile creativity to that of their own.

Cornered in “The Ring” and under pressure from Austria’s café culture, Meisl relented to recall the enigmatic Sindelar but decided to bring in the waif-like playmaker for Scotland’s visit in May 1931. Meisl needn’t have worried. “The paper man” scored his first international goal since 1926 as Austria thrashed Scotland 5-0 and with Sindelar as their unorthodox centre forward, the Wunderteam was born. Over the next eleven games, Austria won nine and drew two, scoring forty-four goals and winning the second Central European International Cup (Gerö Cup). Their style became known as the “Danubian Whirl” and Sindelar was rebranded as the “Mozart of football”. Stephen Tudor described Sindelar as a ‘one-man Vienna Waltz’, dribbling past opponents as if they weren’t there. At the time Sindelar was playing, The Daily Mail declared him one of the greatest footballers in the world and reported that Manchester United even attempted to sign him, for what would have been a then record British transfer fee of £40,000.

Sindelar was a part of the FK Austria Vienna team that won the Austria Cup and Mitropa Cup (the forerunner of the European Cup/Champions League) in 1933 but by the time the World Cup of 1934 rolled around, Austria’s Wunderteam were waning. Austria made it to the semi-final against Italy but, with Sindelar marked out of the game, lost to the eventual winners by a goal to nil. Unable to rouse themselves for the third/fourth place playoff, Austria lost to Germany 3-2. Even though Austria would later win silver at the Berlin Olympics of 1936, none of the Wunderteam were playing.

Albeit not the force they once were, the Austrian Wunderteam managed to defeat England 2-1 in 1936. Mastering his false nine role, Sindelar’s game was paramount as he repeatedly pulled his marker, John Barker, out of position in order to create opportunities for his teammates. During this period, Sindelar also led his domestic side, FK Austria Vienna, to Austrian Cup successes in 1935 and 1936 as well as helping the team win the Mitropa Cup for the second time.

Upon the arrival of the World Cup in 1938, the Nazi’s policy of Anschluss had absorbed Austria into their territories, meaning that there would not be an Austrian team represented at the tournament, despite having qualified. In a similar fashion to the political annexation, the Austrians were informed that players from their team would be incorporated into the Germany team. Sindelar declined to play for Germany citing old age and injury. However, he was persuaded to come out of retirement to play one last game for his nation, in what was dubbed as the “Alliance Game” between Austria and Germany to celebrate the Anschluss. At the insistence of authorities, the match was to end a well-mannered draw, but Sindelar had other ideas.

At Sindelar’s suggestion, Austria played in red shirts – the colour of their flag – instead of their usual white strip. In a first half dominated by the Austrians, a contemporary report suggested that Sindelar had to be openly mocking the Germans because of the number of times he rolled the ball just wide after an exquisite touch, defying the supposed orders not to score. In the second half, Sindelar snapped. He scored the first goal himself and celebrated Sesta’s audacious lob by wheeling around in front of the Nazi functionaries and Austrian VIPs.

Sindelar was dead within a year of the “Alliance Game”. He was found dead lying next to his Jewish girlfriend. The official cause of death was carbon monoxide poisoning, although the cause is debated; it is unknown whether it was accidental death, suicide or murder at the hands of the Nazis. We do know that Sindelar bought a Jewish café after retiring from football, paying a fair price for the business, in direct conflict with the policy of buying cheap Jewish businesses and he didn’t take kindly to displaying Nazi propaganda or taking collections for the party. The building in which he and his girlfriend lived had reported issues with its chimneys, but a picture taken of Sindelar after his retirement shows a man looking like he was about to give it all up. The authority’s decision to sign it off as “accidental death”, without a thorough investigation, only fuelled the rumours that Sindelar had been murdered by the Nazis.

Sindelar was given a state funeral, with tens of thousands of people lining the streets to bid farewell to him. His obituary read – ‘he would play football as a grandmaster plays chess: with a broad mental conception, calculating moves and countermoves in advance, always choosing the most promising of all possibilities’. His contemporaries suggested that he was the perfect mix of effective and aesthetically pleasing whilst Willy Meisl reported that he was ‘truly the symbol of Austrian soccer at its peak period with technique bordering on virtuosity’.

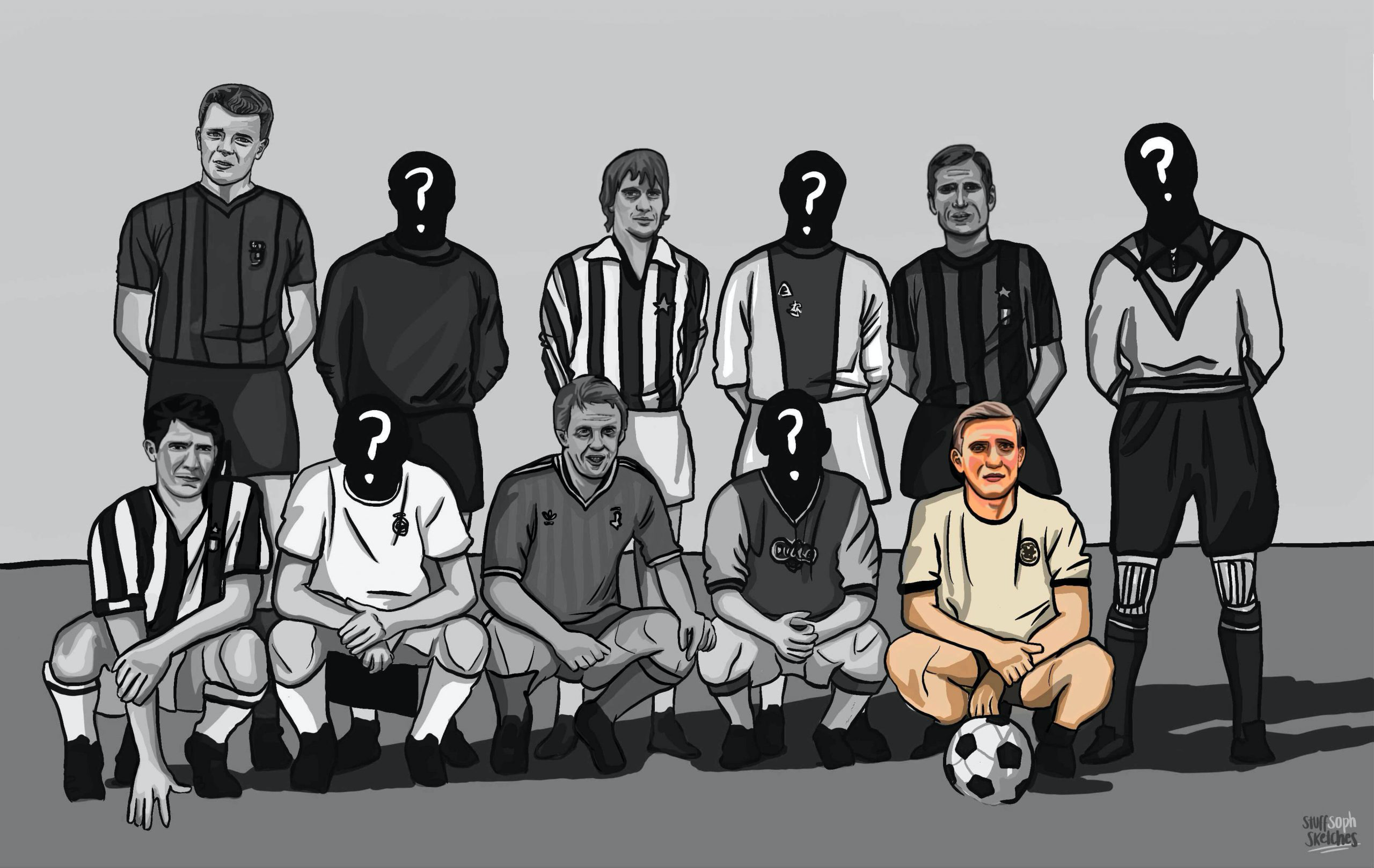

Voted Austria’s Best Footballer of the Twentieth Century in 1999, he ended his career having won an Austrian Championship, five Austrian Cups, two Mitropa Cups and one Gerö Cup in 1932. He scored twenty-seven goals in forty-three international games for Austria and paved the way for a tactical revolution that would be made whole by the likes of Lionel Messi almost eighty years later. He was the darling of the Viennese café culture, seen as the embodiment of their footballing beliefs come to life. But, for all he did achieve, Sindelar should be remembered for the matches he chose not to play, with a nation that was not his own. At a time when other countries (England included) were offering the Nazi salute as a sign of respect before playing Germany, Sindelar’s small act of defiance demonstrates that as important as football is, it is not worth selling your soul for.